It’s safe to say that the city of Reykjavík has undergone considerable changes over the last 15 years or so. New neighbourhoods have emerged, and the city center has, in many ways, been transformed. Icelandic Times sat down with Ólöf Örvarsdóttir, director of Reykjavík’s Department of Environment and Planning, to review the projects, the benefits for residents, and—last but not least—what lies ahead in the near future.

The Department of Environment and Planning oversees nearly everything related to the man-made environment of the city. This includes urban planning, construction, transportation, climate and environmental matters, waste management, managing the Botanical Garden, the Youth Employment Program, and all construction and maintenance work, to name a few. The projects, needless to say, are numerous and diverse.

Building the City Inward, Not Outward

“One of our main challenges at the moment is to increase the supply of residential housing, which is probably the most extensive project today. It’s important to keep in mind that we currently have a lot of approved zoning plans that can soon be built upon. However, favourable loan terms and other conditions need to be in place as well,” Ólöf points out. “The policy of the City of Reykjavík is to build inward rather than outward, as there are growth limits in the capital area, just like in other municipalities. This approach helps utilize infrastructure more efficiently and makes the city more sustainable.”

Strengthening High-Quality Public Transportation

According to Ólöf, the reason for these growth limits in the regional plan from 2015 is primarily that if people can only live in one part of the city and work elsewhere, the need for additional transport infrastructure increases, and as most people are aware, the roads can hardly handle more traffic. “Cities are generally more sustainable if there is a mix of residential areas and employment opportunities,” she adds. “To address the need for transportation improvements, and particularly in response to climate issues, the municipalities in the capital area have made a transportation agreement with the state, in which it was decided to enhance high-quality public transportation. It’s all connected—being able to work near your home, live close to your workplace, access services within walking distance, and having high-quality public transportation, not to mention a dense network of bike paths—improves both health and the overall quality of life for city residents. Let’s not forget that owning a car is expensive, and that cost should rightly be considered part of the overall cost of living. We need to ensure a diverse housing future that aligns with our environmental priorities through planning, in collaboration with stakeholders and the construction industry. It’s a considerable challenge.”

Transport Channel from Suburbs to City Center

Here, Ólöf touches on the pressing issue that has repeatedly appeared in local news in recent years and is commonly referred to in everyday speech as urban densification.

“Yes, the term for this is also what’s known as Transport-Oriented Development, and its manifestation is visible in the form of the transport channel that now stretches from the city center all the way up to Keldur area, which is the next major suburb in Reykjavík,” Ólöf explains. Borgarlína [The City Line, a soon-to-be-realised urban transport system] will run along this channel.

“If we trace this channel from east to west, it will start at Keldnaholt, where a diverse and eco-friendly neighbourhood will soon be established. Next comes Ártúnshöfði, where we are building new developments alongside the old to densify and mix the area. This project is already well underway and will transform into a new neighbourhood, although mixed with what’s already there. Apartments, schools, a cultural centre, exciting outdoor spaces, squares, and more,” says Ólöf. “This neighbourhood will be connected by a bridge to the new district in Vogabyggð, where significant development has been ongoing. A recent design competition for a school and primary school just concluded, with a school building set to connect the two neighbourhoods. There are also plans to put Sæbraut in a tunnel, which will better connect the neighbourhoods on the surface to our old and established Vogahverfi.”

Then we reach Suðurlandsbraut, where Mörkin is located, and in Skeifan, considerable development is planned. A large residential building has already been constructed at Grensásvegur 1.

We continue our virtual tour with Ólöf’s guidance and arrive at the so-called Orkureitur lot, where the Orkuhús building once stood. There is significant development happening here, and more is planned in Álfheimar, where residential buildings are set to be constructed on the site of a gas station.

“If we go a little further west, we reach Ármúli, Vegmúli, and Hallarmúli,” Ólöf adds. “We are working on a development plan for this area where we will slightly increase the height of the buildings to add apartments on the upper floors, turning the area into more of a mix between residential and commercial spaces. Behind the Nordica Hotel, a zoning plan is in progress where more apartments could be added. Meanwhile, a new four-star Hyatt hotel is under construction where the old building of RÚV, the National Broadcasting Company used to be, and just a little further is the Heklureitur area, where hundreds of apartments are being built. Then we arrive at Hlemmur bus terminal, where everything is being revamped with beautiful outdoor spaces and pedestrian streets.”

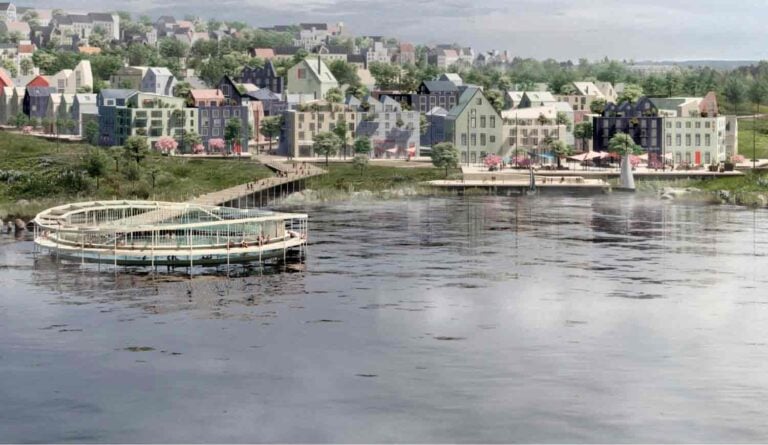

“The route continues down Hverfisgata, where there has already been significant densification with new buildings and apartment blocks. Finally, we arrive at Hafnartorg and Austurhöfn harbour, where numerous apartments have been built. When you put all of this together, we have a densification channel along the public transport routes. All of the aforementioned developments lie along the Borgarlínan line,” Ólöf explains. The number of apartments is higher than in a traditional school district, she adds.

Maintaining Moderate Building Heights

It’s an old and familiar story that while construction companies often want to build as many floors as possible—to fit the maximum number of apartments on a given plot—it is generally considered more people-friendly not to build too high so that sunlight can be enjoyed, and views are not overly obstructed. The most favourable solution for all involved is likely to find a balance between the two. But how will this be handled in the aforementioned projects, where densification is taking place and new buildings are being constructed?

“We’re not building particularly tall structures in any of the projects I mentioned earlier. At Hlíðarendi, we are going up to five floors, possibly six in some cases. At Heklureitur, we’re going up to six to eight floors, with the uppermost ones being set back. Those are the tallest we’re doing. Generally, we’re working with buildings that are three to four or five floors. In selected areas, we’re going up to six or seven floors, and slightly higher around the proposed Borgarlínan stations.”

Urban Design Policy on the Table

Ólöf adds that there is a requirement for sunlight in gardens based on calculations that have been integrated into Reykjavík’s master plan, “so that we have something concrete when negotiating with developers. As for sunlight in apartments, we often want to go further than the building regulations stipulate—which is actually very minimal. In fact, I wish the building regulations were a bit stricter in that regard,” she adds with a smile. “Daylight and sunshine are so precious at our latitude.”

“We’re also quite far along in developing a so-called Urban Design Policy. In this, we’re ensuring, amid the rapid development that’s been taking place, that there will be things like forecourts in front of new buildings and plenty of greenery in every location. If underground parking garages are built, there’s a requirement for thick soil above them so that vegetation can grow and thrive. Ultimately, urban planning is also about flowers and bees. When building new within older areas, it’s more efficient for municipalities and the environment because the infrastructure is already there—like roads, utilities, schools—although sometimes expansions are needed. In contrast, the footprint of development in the suburbs is much larger in every respect, both in terms of environmental impact and financial resources.”

Capital Traffic Volume Unlikely to Decrease

Everyone who drives in Reykjavík and its surroundings is familiar with the heavy traffic that dominates the mornings when people drive to school and work, and then again in the afternoon when it’s time to head home. In light of this new transportation improvement, what changes can residents of the Greater Reykjavík area expect when the Borgarlína (City Line) comes into operation? Is it realistic to expect fewer cars on the roads?

“No, we won’t see fewer cars,” says Ólöf. “I think it’s unrealistic to expect that. However, with Borgarlína, commuters will have an alternative. Our population is constantly increasing, and people are unlikely to stop driving. But hopefully, we will reduce the rate of growth in the number of cars on the roads and prevent the massive increase we’ve seen in recent years. The number of cars cannot grow in proportion to population growth because there simply isn’t enough space for that, and the impact on the environment and public health would be negative. Borgarlína, which will operate every seven minutes and move on a designated lane without hindrance, will be an efficient option for people to get from one place to another. Additionally, bicycle commuting has grown significantly in recent years. These changes, along with well-executed urban densification, are the key to good urban development for the future, which, in my opinion, is the best way to address the current situation.”

Text: Jón Agnar Ólason