Helgi Thorgils Fridjónsson has been one of the most prolific and well-known living painters of Iceland over the past few decades. In addition to his constant exhibitions worldwide, he has operated a private gallery in his home continuously since 1980, mostly introducing foreign artists to Icelanders. And there’s plenty ahead for Helgi, who, as ever, is not sitting idle.

Helgi Thorgils was born and raised in the small seaside community of Búdardalur but moved to Reykjavík at a young age to begin his art studies. Although he took on farm work early, the muse of art visited him early in life, as he recounts to me when we sit down for a chat at his home. Helgi’s corner sofa is adorned with numerous colourful pillows, just as his home is filled with beautiful artworks wherever you look.

“I feel like this started when I was very young, and I don’t really know when I began to be an artist,” says Helgi about his early years. “I had, of course, read Lust for Life [the story of Vincent Van Gogh by Irving Stone] and The Moon and Sixpence [W. Somerset Maugham’s novel partly based on the life of Paul Gauguin], and many other things, and at first, I thought an artist’s life was something like that. These are stories of great artists who gradually become who they are. Gauguin started as a clerk, and Van Gogh intended to become a priest but failed at that,” Helgi adds. “But as for art education”—Helgi pauses for a moment—”in my opinion, an art school doesn’t create an artist, but it can accelerate the artist’s journey because you connect with many things at the same time and with others who have similar thoughts, a process that would otherwise take you an additional five to ten years.”

“Getting Through It—Or Not Getting Through It”

Helgi Thorgils has been drawing for as long as he can remember, although his hands were never idle when it came to farm work, which he was tasked with at an early age. The couple who ran the farm at Höskuldsstadir, where he stayed for half the year from the age of 7 to 13, were born in the 19th century, and both had grown up on farms visited by the English artist W.G. Collingwood when he travelled through the country in 1897. “When Collingwood travelled around the country, he often sketched the children on the farms, so there’s a possibility that somewhere there’s a portrait of the couple as children by Collingwood,” Helgi adds with a smile.

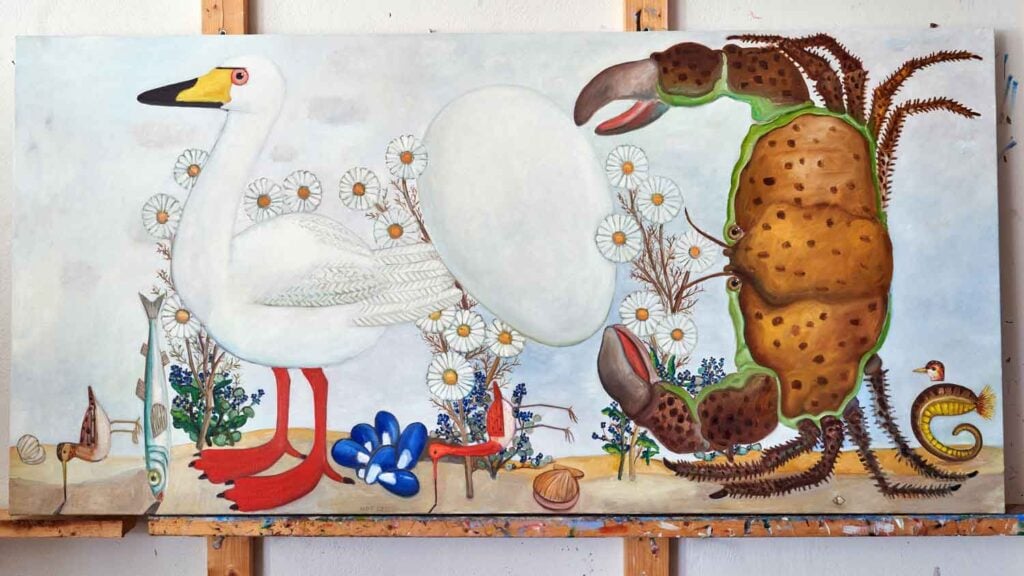

“But I did all the main chores, and I think that when you’re alone, working hard from the age of seven until confirmation, you eventually fall into one of two categories: the kind of person who gets through it and grows from the experience, or the kind who perceives that period negatively. Fortunately, I was always rather solitary by nature. But looking back, I remember that adults always enjoyed talking to me. That’s quite special. There weren’t many peers around to play with in the countryside. But with art, for me, it was always the case that I read a lot and wrote a lot, and my career could have perhaps developed in that direction. In part, I owe a lot to writing because it complements the art in a way that develops many aspects of it, maybe even more so than if I had focused solely on writing. I think this is the reason why I have a rather broad view of art, and my gallerist in Italy once said something that meant a lot to me: ‘Your art is such that one can see the whole history of art, the entire history of humanity, in what you’re doing.'”

“The Passage of Life” from One Place to Another

For more than 44 years, Gallerí Gangur (Gallery Corridor) has followed Helgi Thorgils, quite literally in the hallway of his home. On the National Gallery of Iceland’s website, it states: “Gallerí Gangur is an artist-run exhibition space founded by artist Helgi Thorgils Fridjónsson in 1979 and is probably the oldest privately run gallery in Iceland to have operated continuously since its founding.” The gallery’s operations began in January 1980 at Laufásvegur 79 and have moved around Reykjavík since then, always following Helgi’s place of residence, even with a temporary outpost at Kárastígur 9 in Hofsós, in the north of Iceland, a few years ago. In a way, the gallery represents the passage of life for Helgi.

“Right now, Bernd Koberling is exhibiting here,” Helgi says, noting that since its inception, the Corridor has aimed to introduce contemporary international artists to Iceland. “Gallerí Gangur has had a significant impact on the art scene here in Iceland, much more than people realize, I think. Many foreign artists have taken their first steps in Iceland through this gallery,” he adds. While many artists have long struggled to promote themselves, Helgi has consistently worked to promote others. He suggests that this spirit of collaboration may have roots in the rural life of his childhood.

“This is simply from the countryside as it was back in the day, and I have never accepted anything for hosting exhibitions or selling works at the Corridor, nor have I ever received any grants for its operation. I decided from the get-go that this would never have anything to do with money. All this neoliberalism—one day in the future, people will look back on it as temporary nonsense. That mindset is not dedicated to life in any way. But the Corridor—it is life itself.”

According to Helgi, galleries and exhibition spaces that later showcased the same artists, whose first Icelandic exhibitions took place at Gallerí Gangur due to his personal friendships with the artists, have not always mentioned the Corridor in their promotional material regarding these artists’ careers in Iceland. “But that’s okay,” he says with a sly smile. “I’ve always told all my students and anyone who will listen: Avoid becoming a bitter artist because you’re the only one who will suffer from your bitterness. No one else gives a hoot.” Helgi laughs. “And I have no interest in spending my short life being bitter.”

Showing Up – Facing the Easel

Throughout his career, Helgi Thorgils has been remarkably industrious with exhibitions, both in Iceland and abroad. His solo exhibitions number over a hundred, and group exhibitions are approaching three hundred. He says he’s a creature of habit when it comes to his work, and it’s clear that he doesn’t rely solely on inspiration to bestow him with creativity. “I am always in front of the canvas early in the morning. Kolur and I”—he gestures to his dog—”always go for a morning walk at exactly five, and I’m back here by quarter to six. Then I have some coffee and sit down in front of the easel. The first thing I do is write down some thoughts. Then I start working.”

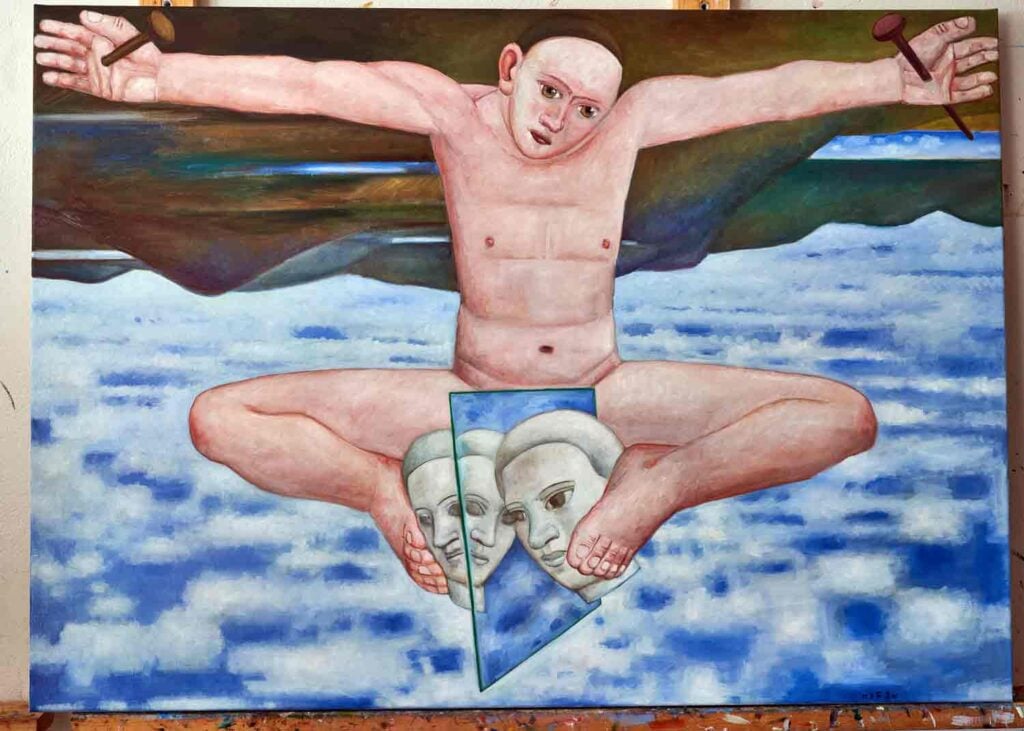

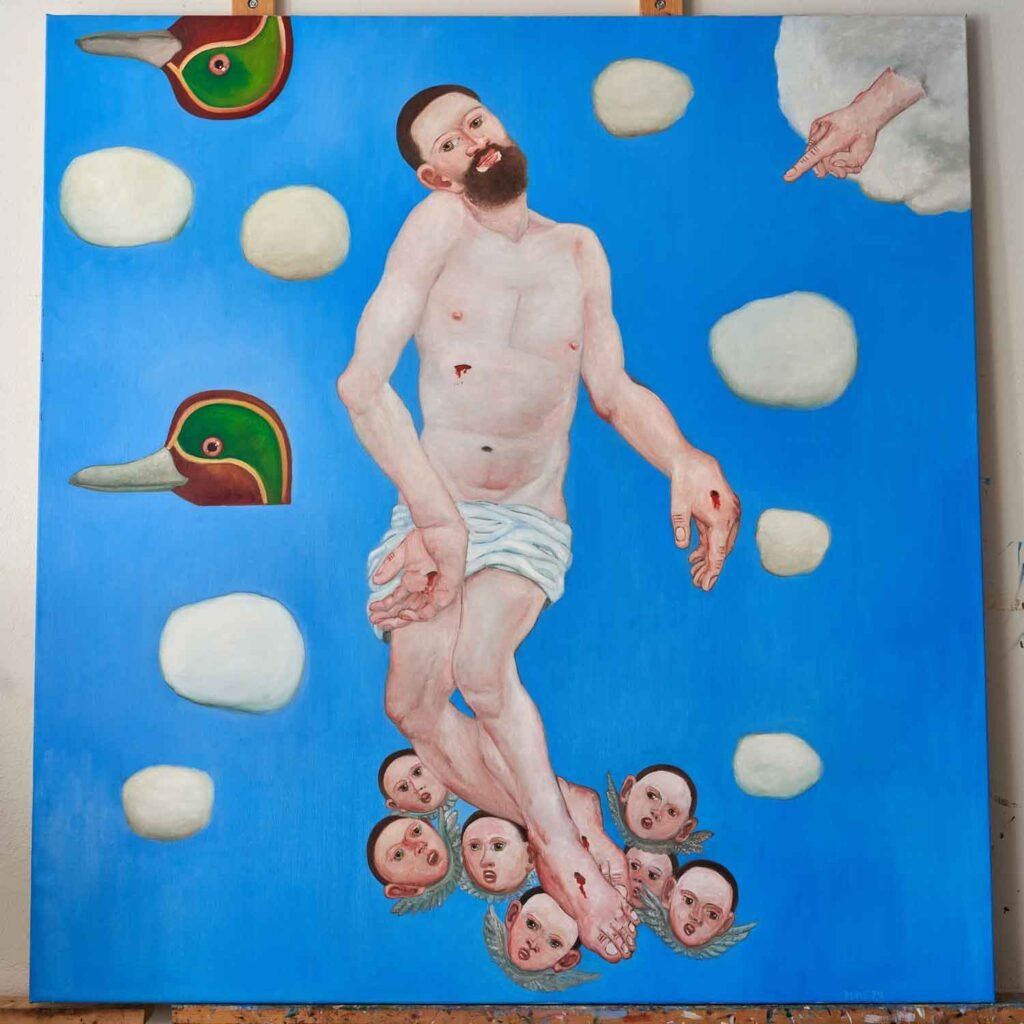

Helgi describes how the ideas and motifs for his paintings, especially the larger ones, often ‘simmer’ in his subconscious for several months before it’s time to stretch the canvas. “Then you look at the canvas, scribble back and forth, maybe with charcoal, and then it starts to take shape and becomes clearer. Then I start working on the pieces, and some people even think my paintings are most beautiful at that stage—when they’re unfinished and expressionistic. Then comes the stage of gradually digging toward the final image, and that’s not always necessarily enjoyable. But all of a sudden, something clicks, and that process might take a week or half a month. At that point, you more or less know how the painting will end up. But in painting, it’s naturally the case that one brushstroke can change the entire image,” he adds, with a thoughtful expression.

Five Exhibitions Next Year – Including One in an Unexpected Location

Speaking of the big picture, it’s crucial for Helgi Thorgils to maintain a good overview of the present moment, as there is much on the itinerary ahead. In an average year, he typically puts up two to three exhibitions, but in 2025, there will be no fewer than five.

“One of the exhibitions will be in an unexpected location, and it’s not quite time to reveal it yet, but it will be in June next year. In January, I’ll have a solo exhibition in Silkeborg, which, of course, is Asger Jorn’s place, and then I’ll have another solo exhibition in Gothenburg. I’ll also be participating in a group exhibition in Germany that opens at the beginning of August, and likely another one in the city of Trento, Italy.”

And lest we forget, Gallerí Gangur will showcase works by notable artists throughout the next year, as per usual. Among them is the renowned Australian artist Jenny Watson, who emerged from the second wave of feminism and has previously exhibited at Gallerí Gangur.

Finally, Helgi sits up on the sofa, resting his elbows on his knees, with his hands clasped tightly. He is silent for a moment with a reflective expression but then begins to speak.

“I want to mention my friend Hreinn Fridfinnsson, who has recently passed away, and I’m going to tell you about our last work together. The morning Hreinn died, I sent him an email inviting him to set up an exhibition in Gallery Gangurinn, as we had often talked about. But Hreinn must have died at the very moment I pressed the button to send the message. Stefán, the husband of Bára, Hreinn’s niece, came to see me around ten that morning for a chat and coffee. He had barely come through the door when Bára called, and Stefán immediately said he had to leave right away—there was something urgent calling him. After he left, I opened my email on my phone, and there was a message from Hreinn’s assistant. She thanked me for the email I had sent earlier that morning and informed me at the same time that Hreinn had passed away that morning. Shortly after, I received another message from Stefán telling me of Hreinn’s death. This cycle is really Hreinn’s fourth exhibition in Gangurinn.”

Text: Jón Agnar Ólason