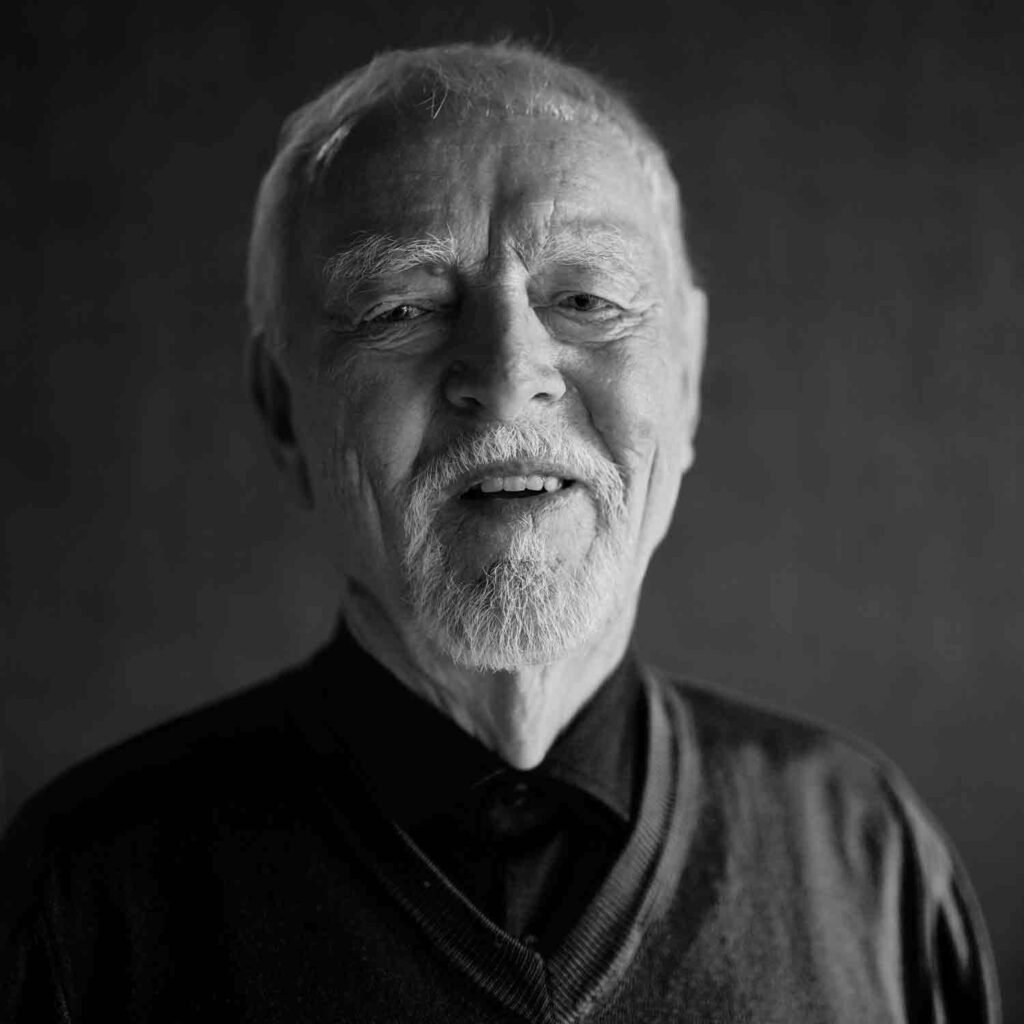

— Interview with Architect Manfred Vilhjálmsson

Manfred Vilhjálmsson is undoubtedly among the most respected and revered architects in Iceland, past and present. His portfolio includes a variety of buildings, many of which are considered some of the most beautiful in Icelandic architecture and have significantly influenced the field in many ways. Manfred invited a journalist from Icelandic Times to visit his home, Smidshús, in Álftanes, where they discussed and reminisced over many aspects of his long career and numerous works.

The atmosphere is somewhat heavy with murky clouds covering the sky on this late summer afternoon when I knock on the door of Manfred’s home, the renowned Smidshús whose name translates to ‘Carpenter’s House’. Somehow, the weather doesn’t seem to affect the appearance of the house; this single-family home, built in 1961, is not only timeless in its design and character, but in its own unique way, it stands apart from its surroundings, regardless of the leaden sky threatening rain. The building’s classic design emanates from its structure. The house is neither particularly large nor multi-story, yet it is incredibly striking to behold, and even more so once you step inside.

Timeless from Day One

“The name of the house is in honour of my father, the craftsman. That’s where the name comes from,” says Manfred as he greets me warmly and invites me inside. I can’t help but feel privileged to walk through the house that I’ve read so much about and often admired in photographs. As mentioned earlier, it was built in 1961, but it’s safe to say that if the house and its interior layout were revealed for the first time today, it would seem just as fresh and perhaps even as avant-garde as it did back then. We take a seat at the dining table, and Manfred offers me a malt & orange soda. Outside, a heavy downpour has started, but inside Smidshús, it’s warm and cozy—something some doubted would be the case when they first laid eyes on the blueprints six and a half decades ago.

“He actually built the house,” Manfred continues once we’re settled with our malt drinks, as he gestures over his shoulder to a portrait of his father, Vilhjálmur Jónsson, a master builder. “He built the house according to my designs, though some of his colleagues weren’t too thrilled when they first saw them,” Manfred says with a grin. “They told my father that he was working on some nonsense his son had come up with.”

As it turned out, the house has hardly aged a day. The same can be said for the house next to Smidshús, called Vesturbær, as both houses were collaborative projects between Manfred and architect Gudmundur Kr. Kristinsson.

Various Innovations Tested

The exterior appearance of these houses is very similar, but they differ on the inside. Although these houses have long been considered classic examples of Icelandic architecture, some craftsmen were sceptical at the time, as mentioned earlier. Smidshús is essentially what you could call an experimental house—Manfred wanted to test various innovations here before trying them out in other people’s homes. One of the main things to note is that only the foundations are made of concrete, while everything else is constructed from lightweight materials. For instance, facing the living room are continuous windows that stretch from the floor to the ceiling, offering a magnificent view to the south toward Reykjanes, with Keilir mountain in the distance. “People had no faith in this setup and said that the neighbourhood kids would smash the windows on the first day,” Manfred says, smiling at the thought. But that didn’t happen, and the glass held.

Manfred continues: “Then there’s the flat roof, which they claimed would never withstand Icelandic weather. But it’s well-built and has never leaked a drop. My father pointed out to his colleagues that the University of Iceland building also has a flat roof. He worked on that building as well. And that settled the matter.” There are also no traditional radiators in Smidshús; instead, it has an air heating system, and Manfred points out the small, elongated vents in the floor beneath the windows.

As I contemplate these remarkable aspects of Smidshús’s construction, I’m reminded of the famous words of another influential architect. The legendary Le Corbusier wrote in 1927—a year before Manfred was born—that houses are machines for living in, meaning that in well-designed homes, everything has to have a function ensuring the best possible living conditions for the inhabitants. There’s some truth to this, but the humanity and warmth of Smidshús are so enveloping that I dismiss this thought, even though everything here does indeed seem carefully considered.

We spend a moment gazing at the vast windows of the south side of Smidshús. Then, Manfred glances back at the portrait of his father, Vilhjálmur, and reiterates how much his father influenced him. “I intended to become a carpenter and even started an apprenticeship with him, working for him for three or four summers. But then I just got sidetracked,” he adds with a chuckle. “But that experience taught me to better understand the craft of carpentry, and hopefully made communication with the craftsmen easier later on, once I began working as an architect,” he says with a half-smile. “Not that I’m necessarily the best judge of that. But it was good knowledge to have in the back of my mind.”

The Years of Study in Gothenburg

Manfred’s buildings carry his distinct signature, whether they are public structures or residences for individuals, located in densely planned urban areas or more natural environments. However, he is reluctant to claim that he always approached new projects with a single, fixed method. On the contrary, he believes that it is most important to maintain broad-mindedness to make the most of each task. In this regard, he emphasizes that, in his view, it is crucial for Icelandic architects to study abroad as well, to broaden their perspectives. He himself studied in Sweden, more specifically at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg. Manfred speaks very highly of his time in Gothenburg, and his expression brightens when he recalls his university years abroad. It turns out that he chose Sweden primarily for practical reasons when it came to selecting a school abroad.

“This was shortly after the war, in 1949, and at that time most countries in Western Europe were damaged to some extent. There weren’t many countries that emerged out of that conflict reasonably intact, except for Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. But when it came to the choice, it was cheapest to go to Sweden,” Manfred explains. “That was really the reason. I also consulted with older colleagues here at home, like Sigvaldi [Thordarson], whom I knew well and who had studied in Denmark. But at the end of the day, I couldn’t afford to go to the United States, and Switzerland was also expensive, as it has always been,” he adds with a wry smile.

“I spent six years in Gothenburg—five years in school and then worked for one of my professors for a year. I could easily have settled in Sweden, but I suppose my wife saved me and brought me back home,” Manfred says with a laugh. “But I was very comfortable in Sweden. It’s quite remarkable that it’s now over seventy years since then, and I haven’t spoken a word in Swedish in seventy years!” He laughs again as he refills our glasses with malt. “That’s not entirely true, but it’s close.”

Adaptation of Buildings to Each Era

When asked, Manfred mentions that he has returned to Gothenburg a few times since his studies ended. He notes that during the preparation for the National Library on Arngrímsgata, he went on study trips to several destinations, including Sweden, Denmark, England, and the United States. The National Library is probably Manfred’s most famous and undoubtedly most extensive work, with construction spanning from 1972 to 1994. It’s worth noting that architect Þorvaldur S. Þorvaldsson was involved in the initial design of the building while the main concept was taking shape, but the final design was in Manfred’s hands. The extensive preparation and construction time paid off, as the building was thoroughly thought out and exceptionally well-executed—something this author recalls fondly from his university years from 1994 to 1996, when countless hours were spent there in reading and studying. The memories are marked by the building’s unique acoustics, excellent lighting, and light woodwork.

In the same way, this description applies quite accurately to Smidshús, even though it is in most respects vastly different from the National Library, both in function and scale. A testament to this is the fact that while Manfred lives alone in the house today—his wife of 70 years, Erla Sigurjónsdóttir, passed away in 2022—there were once eight people living there at the same time, which speaks to the house’s adaptability and practicality. “There was me, my wife, we have five children, and my mother-in-law also lived here for a while. It was an incredibly enjoyable time.” Manfred smiles at the thought. “Now it’s just me here, hanging around,” he says with a laugh. “But it has been an exceptionally good place to live.”

We sit and chat for a while as the contents of the can of malt drink are slowly consumed. The rain has cleared, and the freshly watered Keilir mountain is now visible in the distance. Manfred shows me around the living room area of Smidshús, telling me about the various artworks found there, most of them created by personal friends of his and his late wife, Erla, as he accompanies me to the door. Now that the weather has brightened, Manfred points again to the large windows. “I thought of it a bit like horses in a pasture when I designed the large windows facing south and the small ones facing north. You want to open yourself up to the summer and the southern sun but turn your back to the northern chill.” There’s more laughter, and Manfred Vilhjálmsson and I part ways with smiles on our faces, at the doorstep of the house he designed, and his father built.

Text: Jón Agnar Ólason