Mr. Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, President of Iceland, officially visited Georgia last March along with a delegation. During the trip, the president and other Icelandic guests learned about Georgia’s history and culture, while also working to strengthen Iceland-Georgia relations, particularly in the field of green energy. At the end of the journey, the president penned a post about the visit, which Icelandic Times publishes here in its entirety, with the President’s kind permission.

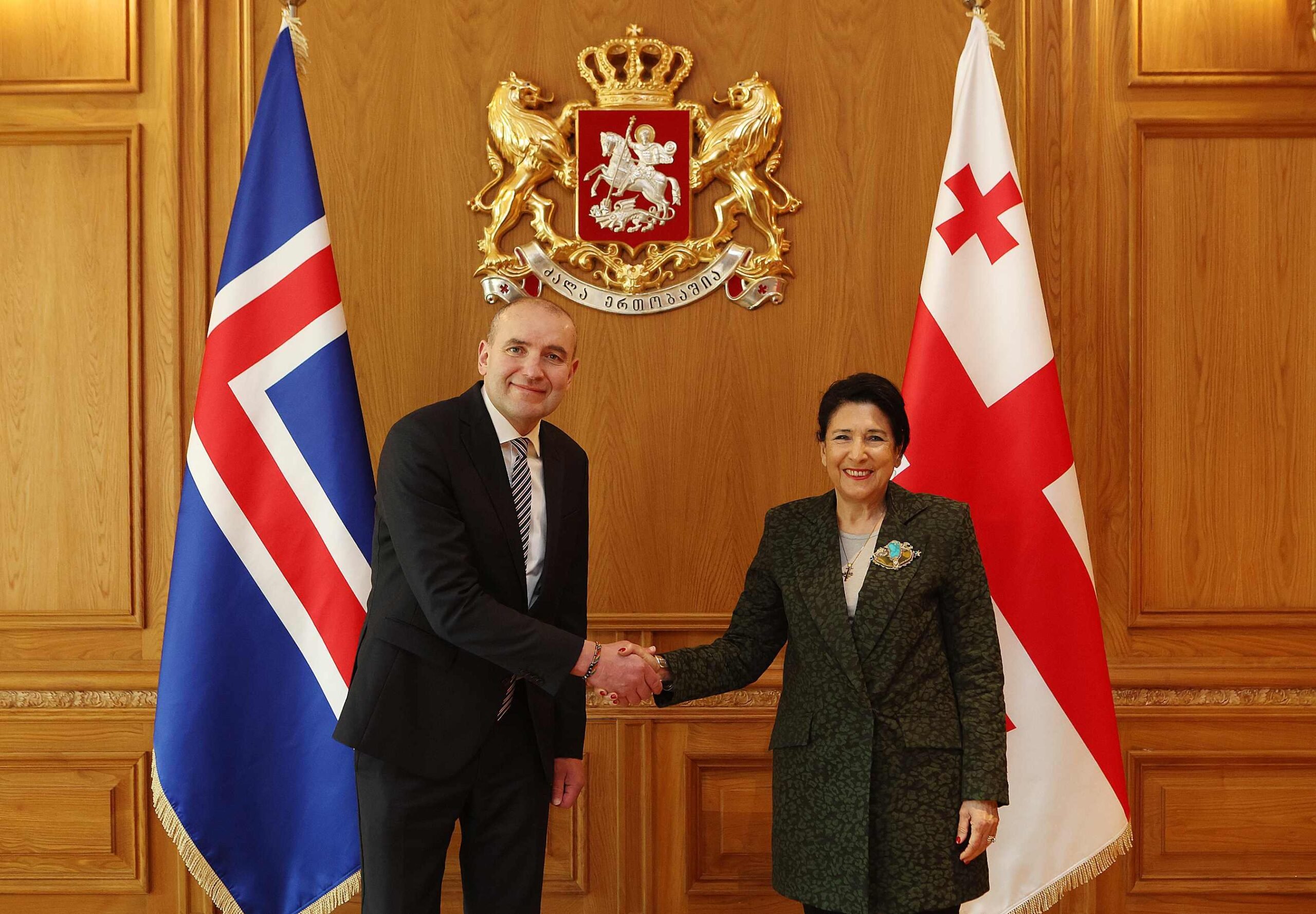

“Now I’m back home after an official visit to Georgia. The trip was successful in every way. Accompanying me was Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson, Minister for the Environment, Energy, and Climate, along with a business delegation led by Nótt Thorberg, CEO of Green by Iceland. Our host, President Salome Zourabichvili, welcomed us warmly, as did everyone else who received us Icelanders in this distant and beautiful country. We learned about its history and culture and worked to strengthen connections between Iceland and Georgia, particularly in the field of green energy.

In Georgia, both geothermal and hydropower resources are utilized, and during our bilateral meetings, there was significant interest in enhancing cooperation between our nations. As a result of this collaboration, the Akhalkalaki hydropower station has been established, marking (National Power Company of Iceland) Landsvirkjun’s first investment beyond national borders. It now provides electricity to around 30,000 Georgian households.

Between Iceland and Georgia, there are also literary connection worth exploring further. Accompanying me on this visit was Bergur Þorgeirsson, the director of Snorrastofa, the cultural and medieval research center named after Snorri Sturluson. Together, we met with the rector and head of the Scandinavian Studies Department at Tbilisi State University to discuss potential collaboration on research related to the connections between ancient Icelandic literature and medieval Georgian texts. One of their prominent poets, Shota Rustaveli, lived during the same period as Snorri Sturluson, and several ancient manuscripts mention Georgia and its surroundings. At the university, I also delivered a lecture on Iceland’s impact on the international stage and had a meeting with the Icelandic Association in Tbilisi.

In Tbilisi, I also gave a keynote speech on security and defense matters. They are highly relevant in Georgia, which is an applicant country for NATO membership, and Icelandic authorities support that application. Approximately 20% of the country is occupied by Russian forces, and I visited the administrative boundary line with South Ossetia. There, I received an overview of human rights issues, as Russians have maintained a military presence in the region since their invasion of Georgia in 2008.

Finally, we had the opportunity to visit the ancient cave city of Vardzia, which was carved into the mountainside in southern Georgia in the 12th century. It once housed hundreds of people when Queen Tamar ruled over Georgia. This remarkable architectural feat suffered significant damage from earthquakes around the same time that volcanic eruptions occurred on the Reykjanes Peninsula a few centuries ago. The preserved portion is now on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, bearing witness to the rich history of this small country in the Caucasus.

I returned home with fond memories and profound gratitude to the people of Georgia for their hospitality.”