“Do you think God created this stone?” This was the poetic question that initiated the sequence of events when Bishop Páll’s stone coffin was discovered in Skálholt on August 21, 1954—arguably the most significant archaeological find in Iceland’s history.

The one who posed this artistic question was a young archaeology assistant, Jökull Jakobsson, as he showed another young assistant, Sveinn Einarsson, a carved stone he had unearthed at Skálholt, the former bishop’s seat. Both of these young men would later leave their mark on Iceland’s cultural life—Jökull as an author and playwright, and Sveinn as a director and head of the National Theatre.

When Iceland regained its independence in 1918, the nation began to revive its ancient culture and history, particularly the Golden Age, which had served as a driving force in the independence struggle. After World War II, attention was turned to the ancient bishop’s seat at Skálholt. A bishopric was established there in 1056, the first in Iceland after the Christianization, and for a long time, Skálholt, along with Hólar later on, was a center of administration, writing, and education in the country. In Skálholt, books were written and translated, the translation of the New Testament began, and some of the largest timber buildings in Northern Europe were constructed, including the grand medieval cathedrals. It was also the site of significant events during the Reformation and home to Iceland’s version of Romeo and Juliet, the most famous and tragic love story in Iceland’s history—the love between Bishop’s daughter Ragnheidur and Dadi. Additionally, the most famous manuscript of Icelandic literary heritage, the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda, was stored at Skálholt for a time after Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson, Ragnheidur’s father, had saved it from being lost.

While it may be a digression from this story, it is worth pointing out that the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda has influenced artists of no less significance than Richard Wagner, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jorge Luis Borges, and even the author of Game of Thrones, George R.R. Martin. And perhaps Marvel’s hero Thor and anti-hero Loki would be mere shadows of themselves if not for the existence of this book!

Now back to Skálholt. There was a desire to restore some of the location’s ancient glory, as it could have been considered the capital of Iceland for 700 years—one of the few urban centres in an agrarian society. Though only ruins remained, plans were made to build a church on the site where no fewer than 10 churches had stood since the 11th century.

It was known that many ancient relics could be found that would shed light on Iceland’s history. Archaeological excavations were therefore promptly undertaken, including efforts led by Dr Kristján Eldjárn, National Museum curator and later President of Iceland.

People believed they knew a lot about Skálholt from ancient stories. One of them, The Saga of Bishop Páll, mentioned that the bishop had ordered a stone coffin to be carved for himself to rest in. This raised the question: could this coffin, along with the earthly remains of Bishop Páll, who was buried in 1211, be found? Or were these old stories from the 13th century mere myths?

But back to the archaeological discovery. After the young Jökull Jakobsson had unearthed what might have been a stone coffin, it was decided to wait for Kristján Eldjárn. When he arrived at Skálholt, he noticed the men were solemn and asked what was happening. “I think we’ve found Bishop Páll,” replied Jón Steffensen, one of the researchers and a professor. Kristján could hardly contain his excitement, and soon they began clearing away the dirt. And indeed, there it was: an impressive, well-carved, and intact coffin.

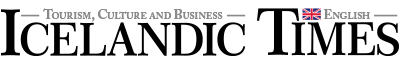

The stone coffin was opened with considerable ceremony a week later in an event that was broadcast live across the country. Priests sang over the ancient coffin, and then the stone lid was drawn off.

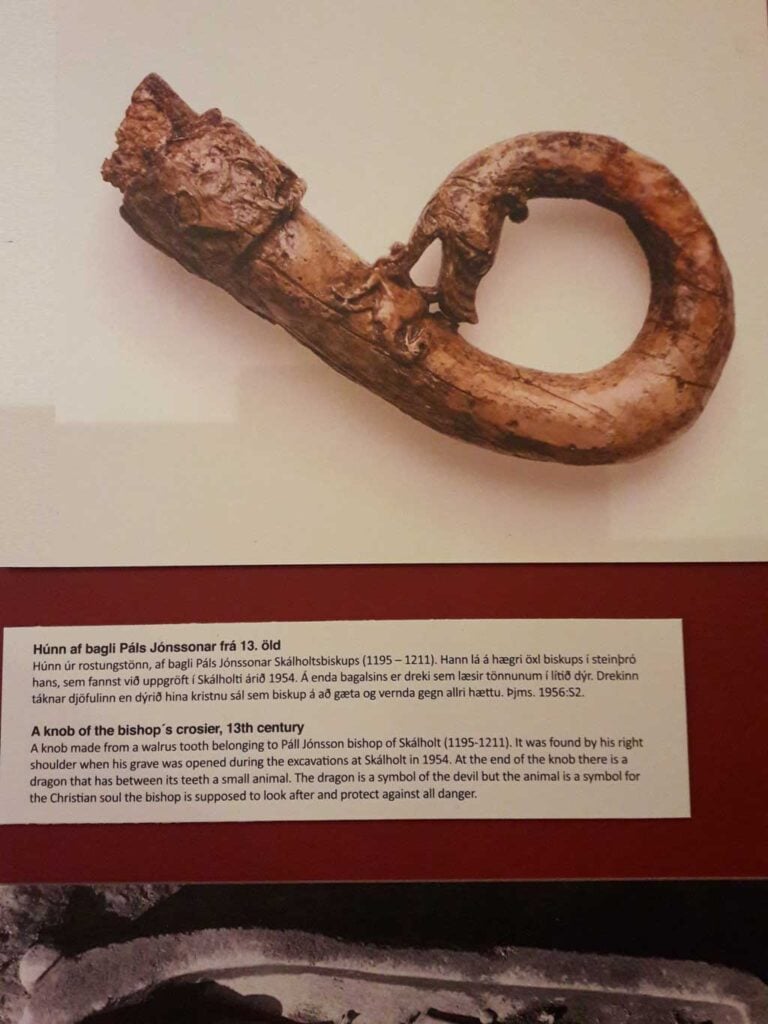

And lo and behold—there lay the bones of the ancient bishop, along with a crook from a bishop’s staff made of walrus ivory. People felt as though they were literally looking history in the eye as they gazed upon the empty eye sockets of Bishop Páll.

But who was this ancient bishop? He descended from some of Iceland’s most prominent families, the son of Jón Loftsson, one of the greatest chieftains of Iceland’s commonwealth era. His great-grandfather was the legendary figure Saemundur the Wise, who was said to have ridden the devil, disguised as a seal, from the School of Sorbonne in Paris to Iceland. His other great-grandfather was King Magnus Barefoot of Norway. He was also a foster brother to world-renowned poet and chieftain Snorri Sturluson.

The bishop’s staff, with its walrus crook, is believed to have been made by the first known Icelandic female artist, Margrét the Skilled, who lived in Skálholt during Bishop Páll’s time. This also points to another fact: walruses were abundant along Iceland’s coasts during the settlement period but were soon driven to extinction.

Bishop Páll’s coffin can now be found in the basement of the cathedral in Skálholt, along with photos from the discovery. The carved bishop’s staff is on display at the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavík.

-Halldór Reynisson