Forging the Future

Forging the Future

The world of tomorrow will no longer be powered by polluting fossil fuels. With the world’s oil and coal reserves dwindling, attention is being focussed on alternative forms of energy generation.

Although a very small country, Iceland is on the cutting edge of both research and use of clean energy resources. The country has shown that it is possible to use clean energy, even close to the North Pole. Whether houses are heated by geothermal energy or powered by hydroelectricity, Iceland has shown that it it not only possible but an environmentally very friendly way to power a modern society. By having the political will, support from the business and academic sectors and an environment that encourages innovation, a lot of progress has already been made.

Whilst, clearly, each country has to assess its own resources and capabilities, if a small nation such as Iceland can develop a renewable energy policy that currently meets 82% of its needs, then larger and more affluent societies can find hope in reducing their dependence on fossil fuels.

Such is the impetus to become as independent of fossil fuels as possible that the development of hydrogen-powered fuel cells is well under way to address the remaining 18% of energy requirements: that of transportation. Experiments with hydrogen-powered buses, methane or electric cars have proven the feasibility of these alternative energy sources. In other areas, recycling has led to towns being powered through energy generated from waste disposal and bio diesel is freely available at fuel stations.

A Worldwide Challenge

A Worldwide Challenge

In this fast-changing world, countries are still heavily dependent on fossil fuels for their energy needs. Afull 79% of current energy needs are met by oil-based products yet, with the developing world’s energy needs growing and oil reserves dwindling, alternative energy forms are needed to fill the void. Presently, all renewable energy forms contribute only 14% of the worlds energy.

According to research published by Dr. Ingvar Friðleifsson, the Director of the UN University in Reykjavik, 70% of the world’s population uses less than a quarter of the energy per capita of W. Europe and one sixth of the USA. Two billion people or one third of the world’s population have no access to energy resources. This is not only a moral issue but a societal challenge of immense proportions, especially given the anticipated increase in the world’s population. A key issue, therefore, is how to improve the living standards of the poor and, in this context, energy plays a vital role.

The only conceivable way to increase world energy supply is to develop renewable energy resources. Nuclear energy, once thought capable of providing all the world’s needs, currently supplies 7% of the world’s energy. It has proven to have serious weaknesses, as shown by the major incidents at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Japan. Nuclear waste is also a very challenging issue, for which no truly safe and effective solution has been found.

Renewable Energy Resources

Renewable Energy Resources

According to figures compiled in 2007, hydro power led the field in installed capacity at 87.5%, followed by Biomass with 4.5%, Wind with 6.6%, Geothermal at 1% and Solar at 0.4%. The potential for each of these resources is so great, however, that all the expected future energy needs could technically be met through renewable resources.

Iceland’s Role

Iceland uses not only its natural resources but the intellect and skills of its people. Since 1951, Icelandic geothermal experts have worked as consultants in over 50 countries in all continents. When the UN discussed the need for the development of alternative energy forms, Iceland stepped up and opened a UN university in Reykjavik in 1978 focusing on the geothermal aspects. Hydrogen use is actively pursued. Wind research is currently under way by a team in the University of Iceland, in collaboration with 14 other organisations throughout Scandinavia, both in academic and business arenas. Tidal energy is also being researched at the university.

Hydrogen Power

Hydrogen Power

In an effort to reduce dependence on oil, Global Energy prize winner, physicist Þorsteinn Ingi Sigfússon and his team at the University of Iceland and Innovation, (the government-sponsored centre to promote development and marketing of new ideas), Daimler-Chrysler, Norsk Hydro and Shell Hydrogen, have already got probably the world’s most crowded hydrogen station in the world running in Reykjavik, currently serving 2,000 cars.

The potential power gains from hydrogen fuel cells far surpass the capacity of current battery storage technology, making them an ideal power source for vehicles. Hyundai is introducing a hydrogen-powered car with a range of 500 km., opening the door for the further expansion of the concept.

Using hydrogen to power fuel cells with battery storage for the excess energy, the vision of the non-polluting electric car is steadily becoming reality. However, there are still great challenges and problems to be overcome but when compared to the amount of time and investment that has been poured into the internal combustion engine, progress has been very significant.

This work is not being done in isolation but is being shared with the international community. An example of this is Russia’s investment in the establishing of a large centre for renewable energy at the university in the 400 year-old city of Tomsk, in Siberia.

Taking another approach, Reykjavik has installed recharging centres for battery-powered cars and the N1 energy company has installed some of its service stations with methane pumps for the increasing number of hybrid cars.

A transportation system whose only byproduct is clean water would have a major impact on the world with a drastic cut in pollution and health issues to name just two.

Using the Fire in the Basement

Using the Fire in the Basement

For many years now, hot water has been used to heat houses in many parts of Iceland. In 1930, geothermal heating was installed in Reykjavik. Bubbling up from the ground in hot springs, the water has also been used in swimming pools and hot tubs. However, it was realised early on that there was potential for much more. Drilling into volcanic rocks, still hot after many generations produced many new sources of hot water and steam. This led to electricity generating stations using this geothermal source to supply power. One unexpected offshoot of one of these stations in the Reykjanes peninsula was the creation of the now-famous Blue Lagoon health spa. By 2009, 66% of primary energy came from geothermal sources – both heat and electricity.

A wealth of experience has been gained in all the technologies needed to tap into this powerful energy source. For the past 30 years, the UN University Geothermal Training Programme in Reykjavik has trained 424 scientists from 44 developing countries from China to Africa to Central America. By training teams who can work together, combining their talents in each discipline, countries can develop a comprehensive development programme. Follow-up is done in each area by the Icelandic professionals and close communication is maintained to provide a cost-effective programme. Geothermal resources offer the most consistent supplies of energy unlike wind and solar power and there are many locations worldwide where the technology can be applied. Its technical potential is 100 times that of hydroelectricity.

Blowing in the Wind

Blowing in the Wind

Wind power generation is a mature technology that is being applied worldwide. However, there is still a great deal of research being undertaken to develop greater efficiency and power.

Iceland, living under the jet stream, definitely has the potential for wind generation. A team, led by Kristján Jónasson, a professor at the University of Iceland, in conjuction with other universities and Scandinavian companies are working on a project named ‘IceWind’. The Icelandic Meteorological Office has built a wind map of the country, showing the most potential sites for wind farms. Landvirkun, the country’s energy company, is planning a pilot project near Búrfell. The wind at a height of 90 m. or more is much stronger and more consistent than at lower levels, so by using tall windmills about 100 m. in height, a much greater generating capacity can be utilised. Developing a complex mathematical model, one plan is to combine wind and hydro to produce constant power. Wind currently produces 2% of world energy. The technical potential of wind energy worldwide is almost 13 times that of hydroelectricity.

Water Power

Water Power

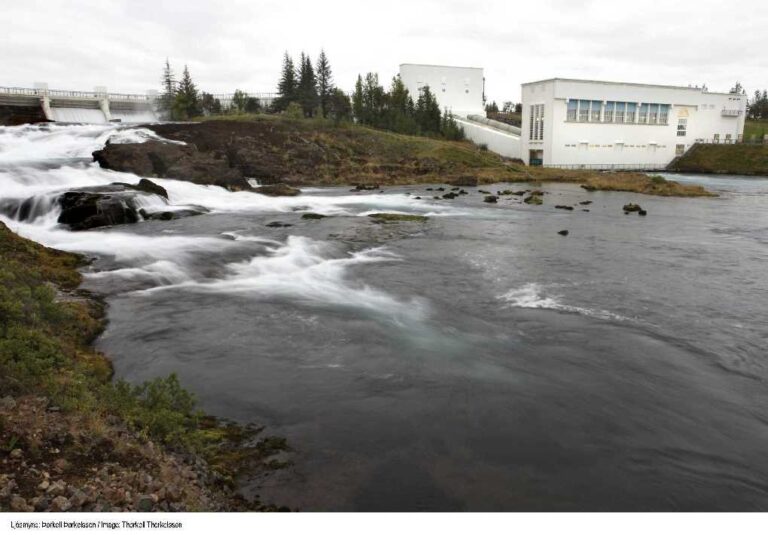

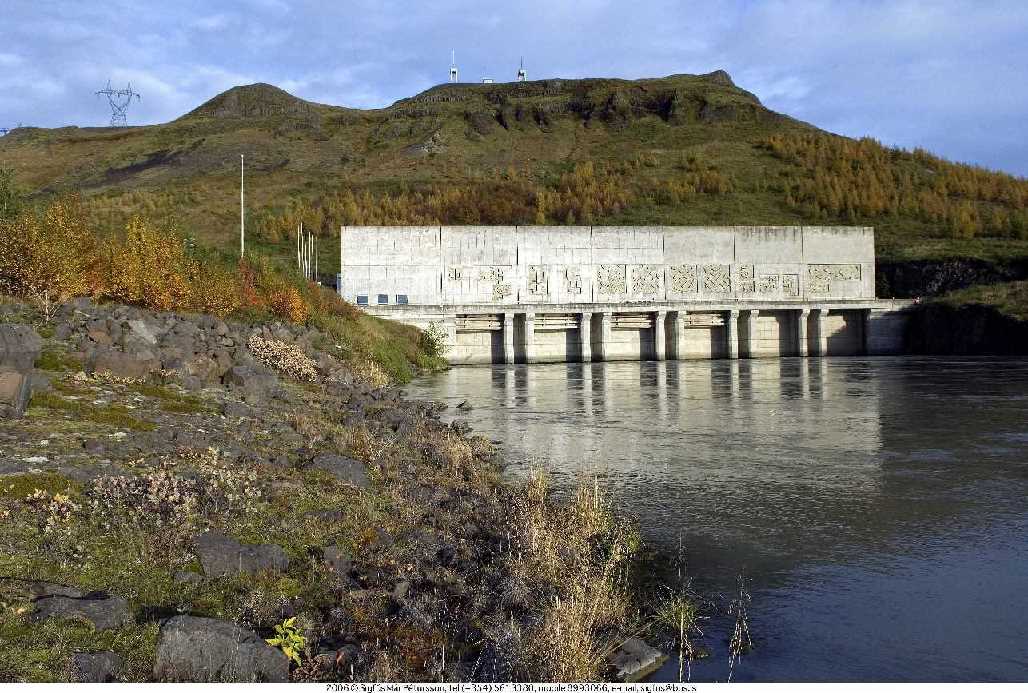

Iceland has some of Europe’s largest glaciers and most powerful waterfalls. The first hydroelectric power station was built in 1904. There are many sites throughout the country that have now been developed for hydroelectric power. Over 80% of electricity generation has been through hydroelectric power. The largest power station by far is Kárahnjúkavirkjun (690 MW), which generates electricity in the area north of the Vatnajökull glacier for the production of aluminium.

Tidal Power

Icelanders are ambitious when it comes to energy and scientists are now looking at osmotic and tidal power to meet future energy needs. Þorsteinn Ingi Sigfusson at the Innovation Centre Iceland (ICI), who has also been involved with the development of osmotic energy and tidal power, says that osmotic technology is relatively safe and simple.

Prototype power plants tapping these innovative sources are to be located in the West Fjords of Iceland and expected to be functional in the next few years. As for tidal power, two types are envisaged. A tidal barrage plant and a tidal current plant.

Bjarni M. Jonsson has been involved with the former. “It will measure the height difference between low and high tides,” he says. He found that the real power that can be harnessed from the fjords emptying into Breiðafjörður would be 75-80 Mw. But there is an added bonus: if the barrage is constructed, two crossings will be built across adjacent fjords to house the turbines. Bridges for these fjords were already in the pipeline by the Icelandic Roads Authority, so the plan would combine both projects.

From Poverty to Plenty

From Poverty to Plenty

Around 1900, Iceland was considered the poorest country in Europe and all its scientists and engineers had to travel abroad to gain their education. Since the end of the Second World War, there has been a massive growth in the university student population and now the University of Iceland is recognised as being one of the top centres of learning and research in the fields of engineering and renewable energy. This, along with the UN University, the new Keilir university at Keflavik and the Innovation Centre, has created a dynamic force for the development of renewable resources both at home and worldwide that will be of great benefit to the international community and developing countries, in particular. From its humble state at the beginning of the last century, Iceland has an understanding of the needs of developing countries and is doing its best to help transform them in the same way.