On a burning face

falls the blue rain

of blue-winged days.

Into the mind’s nullity

night comes

like an untitled story.

And the nakedness of that which is

loses the nearness of itself

in nights and days.

The image that poet Steinn Steinarr sketches here in the thirteenth poem of his series Time and Water is meaningless to conventional reason and falls flat if we try to explain its meaning using logical rules. The language addressing us here points beyond the rationality that tells us raindrops are just water, a face just a mask, a day a number on a calendar. This is a language that points beyond prior definitions of words, to speak the language of images. Moreover, the images formed by these words are not based on any definite model that we can rephrase or refigure for purposes of explanation. The poet’s words and images penetrate our consciousness and leave behind an imprint or wound which we can’t define without falling into a purely banal mundanity from which the fantasies of dream have been excluded, all danger zones fenced and designated off-limits. Nonetheless we are moved. Moved because we feel this image echo inside us; it discloses to us a previously-hidden inner world of our own. This image, so simple that it almost comes to nothing, nevertheless becomes something infinitely big, like the drop that fills the bowl of our consciousness and ruffles the water clear out to infinity …

The image that poet Steinn Steinarr sketches here in the thirteenth poem of his series Time and Water is meaningless to conventional reason and falls flat if we try to explain its meaning using logical rules. The language addressing us here points beyond the rationality that tells us raindrops are just water, a face just a mask, a day a number on a calendar. This is a language that points beyond prior definitions of words, to speak the language of images. Moreover, the images formed by these words are not based on any definite model that we can rephrase or refigure for purposes of explanation. The poet’s words and images penetrate our consciousness and leave behind an imprint or wound which we can’t define without falling into a purely banal mundanity from which the fantasies of dream have been excluded, all danger zones fenced and designated off-limits. Nonetheless we are moved. Moved because we feel this image echo inside us; it discloses to us a previously-hidden inner world of our own. This image, so simple that it almost comes to nothing, nevertheless becomes something infinitely big, like the drop that fills the bowl of our consciousness and ruffles the water clear out to infinity …

This occurs when poets reach the point of making living symbols, symbols that live not for their meaning but for their efficacy alone, the effects they elicit. As the psychoanalyst Jung said, a living symbol is always ambiguous; it points beyond the world of definitions toward the unconscious and unknown and ultimately back toward nothing but itself, since nothing else can elicit its effect. It is characteristic of all poetry to breach the previously-defined outer limits of language; the poet is always situated in the danger zone of delerium in which rationality dwindles and the demons of insanity become imperious, demons of the madness that dwells in each of us, that we know, for example, from our dreams. This is the madness that psychology has called the unconscious core of humanity’s natural urges. “The Ego is not master in its own house,” said Freud, and each person’s daily life is strictured by tension between rational regulation and those fantasies of desire that the poets alone can give form to in their symbols, symbols that lend wings to our desires and dreams. Desires and dreams are the other side of psychic want. We desire not what we have but what we lack. Our desires are the driving force we feed upon; poets lend them wings and help us to perceive them. To recognize our desires and dreams and know how to pursue them is the way to become ourselves. This roadtrip lasts as long as life itself, so long as the desire to live remains. To understand and perceive our desires and dreams we need symbols. Hence poetry is a vital necessity for humankind.

When we have defined a symbol’s meaning it ceases to be a symbol, for definition devours the unconscious and unknown part of the image, strips it of its efficacy and makes it into a sign. It no longer discloses the danger zone of our world of hidden desires, no longer points the way to ourselves. Hence it is vitally necessary for us to renew language, breach the defenses and security systems that stagnant social language locks us into.

The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard has written remarkable books on the psychology of the material world, especially with regard to the elements. At first a title such as his Psychoanalysis of Fire seems provocative; we have been taught that the material world is inanimate. Yet Bachelard proclaims that in relation to humankind nature is a living being, for man not only identifies with nature but is part of it and thus psychoanalyzes water as naturally as he does his neighbour. And in truth, from time immemorial, man has personified natural forces and psychoanalyzed them in myth and religion.

In his book Bachelard makes an important distinction between what he calls the formal and material imaginations. Formal imagination concerns the outward appearance of objects, their decoration and surface; material imagination concerns deeper and more inward material properties, which may concern gender, personal qualities, or an obsession, for example: fire is masculine, like sky, earth is feminine, like water; water tends toward the level, fire toward the vertical; a sunset on the ocean rim joins sky and earth and conveys death and rebirth, and so on.

Contemporary technologised society tends to regard nature and the material world as raw materials for human processing and consumption. In accordance with this view we have been taught that nature is inanimate matter. Steinn Steinarr’s poem series Time and Water, quoted above, shows by contrast a deep understanding of the psychology of water: waters manifest man’s fate. Living water from a spring never rests until it reaches its goal in level ocean: “the pain of water is infinite,” says Bachelard, adding, “In the depths of matter there grows an obscure vegetation; black flowers bloom in matter’s darkness. They already possess a velvety touch, a formula for perfume.” (Transl. E.R. Farrell) The philosopher reaches for poetic language to illustrate his case and might equally have said, with Steinn Steinarr:

but my dream glowed

in a veiled life-ripple

while the depths slept on.

And my hidden sorrow

catches up with you

like a blue-distant sea.

The water in Guðrún Kristjánsdóttir’s round glass bowl rests on black sand on the floor of the narthex of Hallgrímskirkja and is ruffled by drops falling from the ceiling to murmuring notes composed by Daníel Bjarnason. The blueness of the walls envelops it and draws us on through the church itself to the apse where the blue of the windows carries us on out into daylight.

Let us not ask what this installation means, for it is not an explanation of anything, no more than is the poem about time and water. We can search the mythology and theology of waters and spin from them countless parallels and references that might be historically informative: stories of purification, death and rebirth, stories about the water of life and milk of earth, stories about water as the image of anima and the bowl as maternal womb or milk-swollen breast, stories about ruffled water as the spirit stirring from above, about the healing springs of Asclepius and Mary and the pool at Bethesda in the Gospel of John: all these stories of the psychology of water are relevant to this image, and yet this image ultimately refers to itself. It is an attempt to fathom the imaginative power of matter that ultimately is our own imaginative power, a signpost on the way toward becoming ourselves.

Ólafur Gíslason (transl. Sarah Brownsberger)

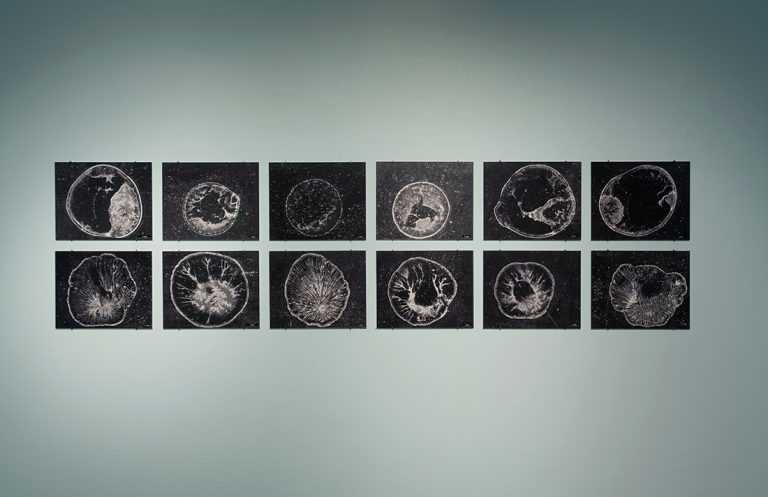

Symbolic of the water and life cycles, water drips into a transparent bowl that rests on sand. Light and musical notes are cast onward as the water ripples. The walls of the narthex are painted blue, color of water and the Virgin Mary. Blue also comes to dominate the 45 lower windows of the apse, underscoring the natural blue hue. A series of photographs presents the results of an act of performance art.

Tap water was put in a bowl. Six specimens were taken from it and placed on glass slides. The water in the bowl was then consecrated and the people present sent good thoughts to it. After the consecration, six more specimens were taken. Once the 12 specimens had dried out, they were examined and photographed under a microscope. Each drop had its own structure, but the consecrated ones had in common that they were all structured from the center. The results are shown unamended.

Integral to the work is music composed by composer Daníel Bjarnason and performed by Frank Aarnink on a stone harp made by artist Páll from Húsafell. Headphones available in the exhibition space feature a presentation about the artwork. © Guðrún Kristjánsdóttir | All Rights Reserved

www.gudrun.is

Vatn

Exhibition

Hallgrímskirkja | 2013

Installation

Photographs, installation,

music by Daníel Bjarnason.

Text

Ólafur Gíslason