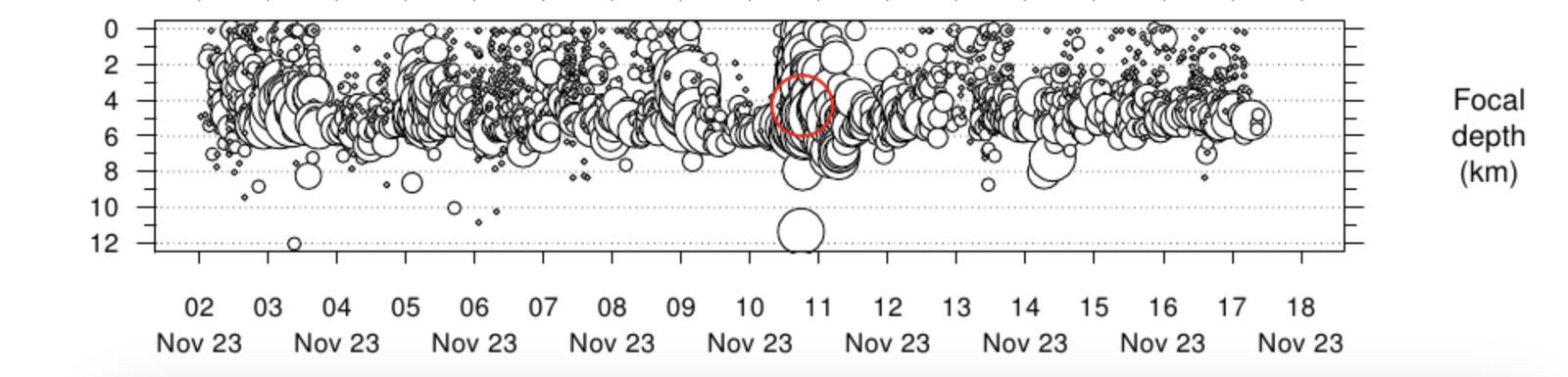

A number of questions arise in connection with the upheaval under Reykjanes. One of the facts that is remarkable is that all the earthquakes that are now happening in Grindavík are shallow, as the picture shows. There are almost no earthquakes measured at depths greater than 7 to 8 km under Reykjanes. The Earth’s crust under Reykjanes seems to be quite thin, like an oceanic crust.

What information do we have about the thickness of the crust and the temperature under it in Reykjanes? We know, for example, from the geothermal drilling that it heats up very thoroughly in the lower part of the earth’s crust on the outside of Reykjanes. When the Reykjanes deep well was down to a depth of about 4.5 km in 2017, the temperature had reached about 535 oC and was rapidly increasing when drilling stopped. Geological studies show that temperatures have even reached 650 oC near the bottom, but the rock needs to go well above 1000 oC to start melting.

Most of the physical characteristics of a rock change when the temperature rises, and science talks a lot about the change in the properties of a rock when it heats up and changes from a hard and solid rock to a warm and soft rock. Scientists call this brittle to ductile transition. Some say that the change starts at about 550 oC, while others believe that rock becomes soft only at about 700 to 800°C, which is more likely. As soon as the rock heats up to this point and becomes soft, the rock stops carrying seismic waves altogether. They die out and disappear in this heat and depth.

Let’s look back to the crustal break and the drift valley at Grindavík. Why do no earthquakes occur at greater depths? It can be caused by two things. We know that beneath the Earth’s crust, we have the mantle and it is too hot to break and cause earthquakes. Under the crust, at a depth of more than 8 km, there is a completely different world, which is the world of the mantle, which extends about 2900 kilometers into the earth, or all the way down to the surface of the core. The other possibility is that under the 8 km crust there is a layer of basaltic magma, but all earthquakes are suffocated in such a layer.

It’s really striking, I think, that all earthquakes die out when you get down to a depth of about 8 km. The boundary between the earth’s crust and mantle is unmistakable under Reykjanes, which reminds us thoroughly that the cause of all these things must come from the mantle, and it is too hot to break like normal rock. There is, after all, movement and pressure in the earth’s crust, which causes the crust to break and send out earthquakes. However, the mantle is partially molten, which means it is partially completely molten magma. It’s perhaps not a very good analogy, but you can think of the mantle as wet sand at the beach, where a thin film of sea water lies between the grains of sand. Similarly, the mantle is wet, but there is a very thin film of lava magma that penetrates between the grains of sand or crystals in the partially molten mantle. The lava magma is created there.

Text: Haraldur Sigurðsson