The title of this extensive exhibition refers to the Icelandic highlands and certain ideas regarding them which Icelanders have long held aloft. It hints at remote wilderness and untamed nature where the footprints of man are rarely seen. Of course, people’s attitude has undergone serious changes through the years, with better access to the highlands and its multitudinous use. Despite this, there is still a tendency to preserve the image of the highlands as an unspoilt area. For more than a century, this no man’s land has been the subject of artists. At any given time they have reflected the different views on the Icelandic wilderness and been instrumental in shaping said views.

Kjarvalsstadir

The Icelandic highlands as subjects of art appear in text before image, in the nationalistic poetry of the 19th century, for example. This was followed by photographs and shortly thereafter also paintings. The first photographers travelled around the country, taking photos of remote places, showing the nation a new side of the country as they readily shot unique natural phenomena and landscape. For centuries the highlands had been a hazardous area which no one dared enter, except to get from one place to another. The work of these photographers aroused a previously unknown interest and reflected new attitudes. Their photos gained popularity and were used in local as well as foreign travel books. The photographers’ view of the country laid the foundation for people’s first graphic knowledge of Iceland’s untouched nature. From then on it is debatable how untouched it was, as the artists had already marked it.

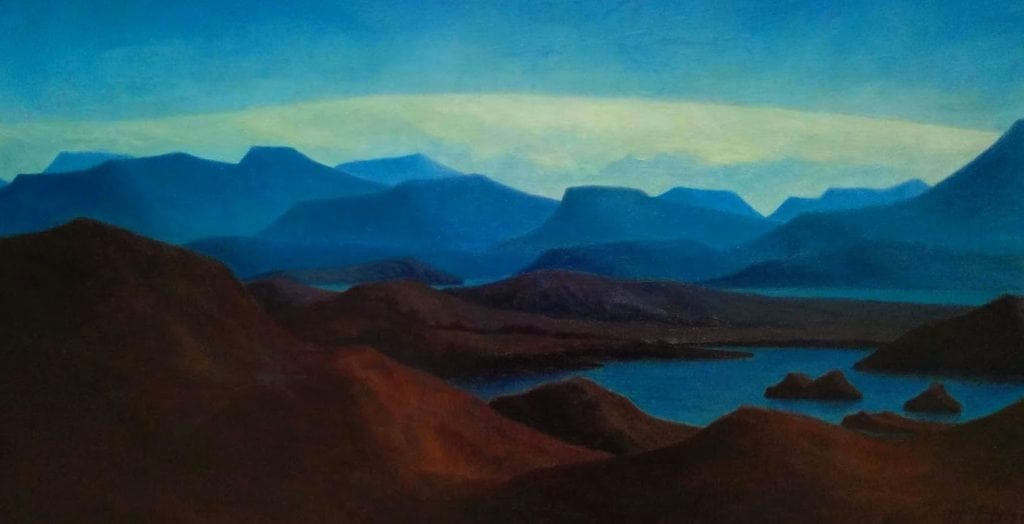

Shortly after 1900, artists Þórarinn B. Þorláksson and Ásgrímur Jónsson went on separate journeys into the highlands. They returned with images of an almost otherworldly landscape. It was distant, calm and shrouded in mystery. Thus the first paintings of the highland landscape are not very lofty or sublime. Much rather, they are in a way realistic, because they reflect the wilderness’s status among the navtives at the time. People had no business here, the nature was totally alien to them.

In the beginning, artists only rarely travelled into the highlands. When great mountains appear in paintings from the start of the 20th century, more often than not they are painted from a safe distance, a view of the glaciers and wilderness from the security of the farmyard. The mountains are the background of the typical landscape, showing flourishing countryside and active environment in the foreground.

In the beginning, artists only rarely travelled into the highlands. When great mountains appear in paintings from the start of the 20th century, more often than not they are painted from a safe distance, a view of the glaciers and wilderness from the security of the farmyard. The mountains are the background of the typical landscape, showing flourishing countryside and active environment in the foreground.

The artists themselves were born and raised in this same countryside. Kristin Jónsdóttir, the first Icelandic woman who dedicated her life to fine art, travelled fairly widely in search of inspiration for her landscapes. She and her contemporaries sought to capture the moment. Weather and light played a significant part in the process, as did the colours of nature. Those impressionistic landscapes revealed a personal relationship between man and nature with a fresh and individual view from each artist.

Artists often painted outdoors to capture the environment’s spirit straight onto the canvas. Of all the artists working outdoors, one of them is by far best known.

Johannes S. Kjarval has a unique position among those painters who dealt with the Icelandic wilderness. He had a deep knowledge and understanding of nature and interpreted it in his own, personal way. Time was an important factor in his imagery, sometimes within the same painting, or in repeated subjects over longer periods of time. Kjarval also played around with his ideas of landscape by adding figures, delving underneath the surface in almost a surrealistic fashion or defamiliarising it in symbolic fantasies.

Johannes S. Kjarval has a unique position among those painters who dealt with the Icelandic wilderness. He had a deep knowledge and understanding of nature and interpreted it in his own, personal way. Time was an important factor in his imagery, sometimes within the same painting, or in repeated subjects over longer periods of time. Kjarval also played around with his ideas of landscape by adding figures, delving underneath the surface in almost a surrealistic fashion or defamiliarising it in symbolic fantasies.

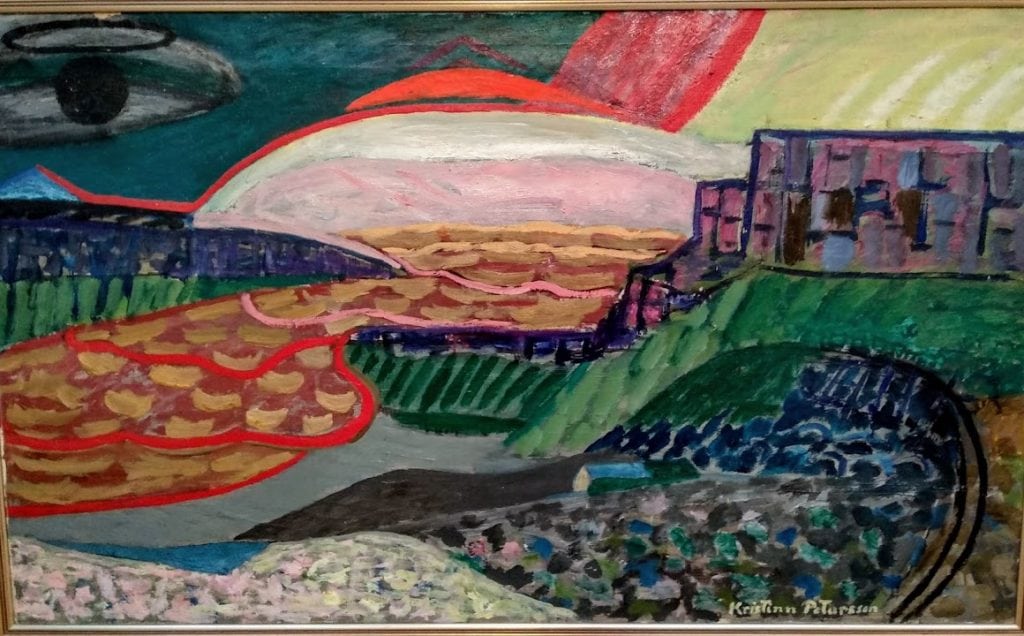

As in Kjarval’s work, other Icelandic painters were also influenced by currents in European art. Thus the barren wilderness were the model for Jón Stefánsson’s experiments with unusual form and composition. He sought inspiration all over the country but the painting itself was the driving factor, so he was not shy to make things up, simplify them or move them around to make it work. Exact conditions were also deviated from in Júlíana Sveinsdóttir’s paintings, to enable her to express her experience of colours and light in the landscape in simple forms and clear composition. Over time, her focus on details diminished and the work mostly reflected atmosphere.

Gudmundur Einarsson from Middalur was quite the mountaineer and ventured far off the beaten path. His view on the landscape was of a new and different nature. His interest in the outdoors was reflected in his art although he normally painted in his studio after he’d finished his travelling. He preferred to deal with the country’s forces of nature, such as eruptions, geothermal heat and glaciers. Guðmundur was fond of exaggerating and didn’t stay too true to the original landscape if he needed to diverge from it to create a stronger painting, more indicating of nature’s powers. Sveinn Þórarinsson shared Guðmundur’s interest in mountaineering and painted various pieces showing the highlands. The wilderness presented a challenge to these artists, as well as being an area of exploration. Their highland journeys also reflect the spirit of the times, where outdoor activities were considered beneficial for body and soul.

Finnur Jónsson and Kristinn Pétursson searched for unusual phenomena in Icelandic nature, craters, geysers and the like, and put their own expressive spin on them with bright colours and exaggerated forms. They also did abstract work and their stance on how to interpret nature was very liberal.

As the 20th century wore on and pioneers in the art of painting had shaped the progress of the landscape tradition, artists’ interest in the subject decreased somewhat. Abstract art became dominant and although influenced by landscape and nature, not many artists worked on the subject in a purposeful manner. A few of them did however show influences from nature in various abstract experimentation. Few artists took their visual simplification to the same length as Stórval. He painted hundreds of paintings of Mt. Herðubreið and and the view of Möðrudalur and its surroundings, all quite similar but show a sincere affection for the subject.

Eirikur Smith was a versatile artist who started his career in the middle of the abstract whirlpool. Gradually his focus shifted and his work became more naturalistic. He travelled all over the country and preferred to paint on site, with the landscape in front of him. Ragnheidur Jónsdóttir Ream presented an unusual viewpoint, almost as if she were gliding over the land at low altitude. Her work also toes the line into abstractionism but the influence of the vastness of the landscape is clear. Þorbjörg Höskuldsdóttir used perspective and geometry to exaggerate the forms and dimensions in the landscape. In her paintings, mountains and wilderness meet colonnades and marble floors. Guðrún Kristjánsdóttir has always spent a lot of time in the highlands and this is visible right from her very first work. She simplifies the land¬scape to the extent that nothing is left except an image of a horizon, mountain, a sandy desert or strip of a glacier.

The avant-gardists of the sixties and the seventies turned their back on the landscape tradition, focusing on the society, history and language.

If they happened to seek inspiration outside contemporary culture, cosmic dimensions and philosophical musings were closer to their heart than the Icelandic highlands. Even though a new movement, land art, emerged in Europe, it didn’t reach these shores, where one would’ve thought our wilderness was a perfect scene for such experiments, A generation gap had formed. The young people came from the city and had no particular affinity for the countryside, rural areas or the highlands. International awakening regarding environmental issues and man’s influence on nature made its way here, with debates about wind erosion and soil reclamation. The idea arose that Iceland was for the most part a man-made desert. The occasional eroded ridge appeared in art exhibitions but the highland’s barren landscape inspired few.

Again it fell to the photographers to renew people’s interest in the no man’s land. They started publishing photos of remote locations in newspapers, magazines and books. This time, actual place was of less importance, the focus was on geological formations, erosion, light and weather. The photos showed a country which was different from people’s ideas, the landscape felt alien and unspoilt. At the same time people started paying attention to the land through the television. The Icelandic National Broadcasting Service brought the wilderness to the people’s living rooms with images and stories which burrowed into the nation’s consciousness. Icelandic filmmaking gave even further rise to a new attitude towards our wilderness at the end of the 20th century. Public interest in remote locations grew and people became more interested in the unique landscape and nature of the highlands, even if they’d never been there themselves.

Hafnarhús

Since the turn of the century, the Icelandic highlands have been the subject of many artists, as opposed to the prevailing trends of the previous years. Some people have dedicated their careers to covering this subject. Their individual focus is on different things but they overlap in many ways. There is a clear tendency to catalogue things, the artists research, analyse, measure and look at the land as it is, but also at its history and utilisation. Many of them are driven by a desire to protect the wilderness against irredeemable harm and employ their art for that cause. The situation has certainly changed within just a hundred years, in the past man was frightened of the highlands, today the highlands are threatened by man. The wilderness has become a research centre of sorts, for artists who are exploring man’s connection to nature, they view it as the modern man’s natural resource in the search for themselves and a renewed connection to the earth.

Although not many artists were found in the highlands in the second half of the 20th century, other people were travelling there at the time. The wilderness was mapped out with regard to possible hydroelectric installations and utilisation of geothermal areas to produce electricity. Ambitious ideas arose, some of them came to fruition and simultaneously the people’s environmental concerns previously mentioned kept growing. The nation’s value of the highlands was transformed. Young artists, Húbert Nói and Georg Gudni, who worked at hydrography, staying in the wilderness for long periods of time, were captivated by their sur¬roundings. They interpreted their experiences in a unique fashion, a total reversal of the old landscape tradition. The landscape and the view were less important than the feeling of the land. The emotion pointed inwards, the artist’s perception, experience and memory opened up for the viewer another feeling of place and space in the vast wilderness.

A hint of this kind of mental landscape is also found in the work of Katrín Sigurðardóttir who has created situations which emphasise how individual each person’s experiences are. Each of us conceives their own landscape in a constantly renewed relationship between man and nature.

The interest in cataloguing and measuring the landscape may have risen from the knowledge that the unspoilt nature is neither eternal nor unwavering. Road building, power plants and other construction projects could transform the landscape, thereby losing things which had previously been taken for granted. Early on, Kristinn E. Hrafnsson went around with his yardstick, at the beginning of the nineties he mapped the surface of all the biggest lakes in the country. By then, many of them had already become a part of a controlled, man-made land¬scape where power stations at their outlets control their size. Mapping is also a key factor in the art of Einar Garibaldi who uses historical maps of Iceland, where it is divided into different parts. By rotating and mixing up the parts, the artist reminds us that the more precise and detailed our images of the land are, the harder it is for each of us to see it as it really is.

Anna Lindal and Unnar Örn both are interested in surveying, each in their own way. Ever since Anna started going on trips with the Iceland Glaciological Society, twenty years ago, she has focused on how man catalogues, watches over and measures the wilderness. She often visits places where scientists are dealing with changing landscapes or even new and unknown territories which have been formed in eruptions or emerged from receding glaciers. Anna’s photo series shows different equipment at different places, automatically and digitally registering changes in the landscape. Unnar Örn also follows in the footsteps of scientists in the highlands, but in this case they were travelling there over a century ago. The first photographs of Icelandic wilderness were shot during the journeys of Danish and Icelandic explorers, around the same time as artists started capturing them. The photos show the land through the eyes of the researcher, show various phenomena in nature and to help the viewer better understand the subject, a person stands somewhere within the frame to show the proportions in the landscape.

The proportion of man and the wilderness is all relative in the photographs of Pétur Thomsen, For years he documented the largest industrial project in Icelandic history, the construction of the Kárahnjúkar Dam. His large photos show a transformation process where men and machinery shape the rough and wild nature. This project was extremely controversial in the society, much more so than previous dams in the highlands. Artists played a big part, they rose up to protect the nature, not only in their work but with direct action and participation in the public discussion. Photographers showed pictures of areas which were threatened with destruction and artists led groups of people on hikes and performances. The public’s at-tention was drawn to the uniqueness of this remote and unspoilt territory. Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir was one of those who stayed for long periods of time at the roots of the glacier, in so-called Kringilsárrani which disappeared beneath the dam’s reservoir. A decade later she revisited the area and went on foot around the reservoir, filming her experience to create an extensive installation.

The fight for the conservation of nature is reflected in many of Rúrí’s works. Her signature subject has been the waterfalls, they represent an untamed natural force which is damaged or destroyed when the rivers are dammed. She has catalogued the rivers, taken photos and filmed, recorded sound and shared this in various ways in her works and installation. Just like Rúrí, Steinunn Gunnlaugsdottir was prominent in the Kárahnjúkar protests, both artists in-stigated direct action and artistic performances. In a new piece she portrays the modern man who is perpetually connected to a digital reality where all your view of the world is concentrated on the same level. The human need which the nature in the vast highlands may once have satisfied is now fulfilled in a virtual reality, in a world which is sustained using the energy which is harnessed at the nature’s expense.

The boundaries between the man-made and the natural are very unclear in today’s discus¬sion on the Icelandic highlands. It has been argued that there is no unspoilt area left, as man has influenced it all through construction and also indirectly in connection to the so-called Anthropocene. In her art, Hekla Dögg Jónsdóttir has explored the nature of experience, in particular of impressionability. She recreates things which have an undeniable effect on us, such as a natural waterfall. By recreating it in the exhibition hall, using lights and sound, she makes an impression on the viewers, which are torn between their memories of the real thing and the present perception of the copy.

Ragna Róbertsdóttir works in a similar way with the boundaries between natural and man-made environment. She collects her materials directly from the nature and treats it so she can use it for her work. She tailors her pieces to the exhibition space, focusing on the viewer’s experience on the spot. At the same time, the enigmatic pow¬ers of the material are transported into the art work, as well as a historic reference when a certain volcano is mentioned in its title.

Ólafur Eliasson approaches the Icelandic wilderness through series of photographs where he captures a defined area from different angles, splits a large unit of land into several pieces or explores the same place for a certain amount of time. Glaciers and glacial rivers appear in his work as ever-changing natural elements, reminding the viewer of the transforma¬tion processes in our environment and how our perception constantly adapts to new situations. The instability of the environment is clearly visible in the photographic works of Hallgerður Hallgrímsdóttir who uses found photos to create her art. She collects screenshots from surveillance cameras from all over the country to follow the conditions of the mountain roads and possible tremors in active volcanoes. Her photos show us yet another new connection between the people and the wilderness, different from the position of old, based on different times and technical progress.

As a young man, Einar Falur Ingólfsson accompanied his grandfather, driving sheep up to Kjölur, thus witnessing from first hand past generation’s connection to the highlands. At the same time he experienced the highlands through the lens of the modern man, aware of all the different attitude towards the wilderness. As a photographer, Einar has travelled the highlands for years, searching for people who venture up there for private reasons.

He meets individuals who each have their own expectations and perceive the environ-ment in a personal manner. In his photos we see those people, but also signs of their existence, the traces they leave behind. The photos reflect extremely mundane needs like shelter, mode of transport, toilet facilities and food supplies – always with the amazing beauty of the wilderness in the background. The physical connection to nature which is present in Einar’s work is portrayed differently in Sigurður Guðjónssons video installation. He is located in a canyon where there are traces of an old concrete dam which has long since burst and the river flows on unhindered. A person shuffles along the old dam wall in a snowstorm. It feels like all speculation about the multi-layered relationship between man and (un)spoilt nature can be attributed to this person, wandering in a kind of limbo.

Where beauty alone reigns?

Man has made his markall overthe Icelandic highlands, but at the same time more than a century of art history shows us that the highlands have an unquestionable effect on man. In World Light (1937-1940), Halldór Kiljan Laxness’s novel about the poet and pauper Ólafur Kárason, the author describes his search for beauty: “Where the glacier meets the sky, the land ceases to be earthly, and the earth becomes one with the heavens: no sorrows live there anymore, and therefore joy is not necessary: beauty alone reigns there, beyond all demands.” Is it really the case that nature and landscape are the abode of beauty and if so, what does the beauty in question entail? Where does mankind enter into this equation, or doesn’t it belong in no man’s land? Popular culture of recent years has shown us an unusual and particular position towards the Icelandic highlands. Movie makers increasingly seek to use Icelandic nature as background to fantasies which are supposed to take place on other planets or in the wake of a major disaster. What does this tell us of the present day’s view on nature – is it still as alien and distant as it was to the artists who first captured it over a century ago? The art work in this exhibition shows an ever-changing connection to the wilderness and that each period has its conflicts. However, the highlands are always present as part of life in Iceland, they shape our identity. They have represented danger and threat, glorified desire for beauty, nationalistic patriotism, thirst for exploration and adventures, energy and prosperity, identity and branding, restand refreshment, a source for the imagination and the list goes on. We shall continue to look to the mountains and let our minds wander.