The unconscious text is already a weave of pure traces, differences in which meaning and force are united—a text nowhere present, consisting of archives

which are always already transcriptions. Originary prints.

—Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference (1967)

In Writing and Difference, French philosopher and theoretician Jacques Derrida clarifies his concepts of the trace and the supplement. He speaks of the “unconscious text” as an ideal where meaning and force are conjoined, and yet spectrally absent—file cabinets filled with copies of “originary prints.”

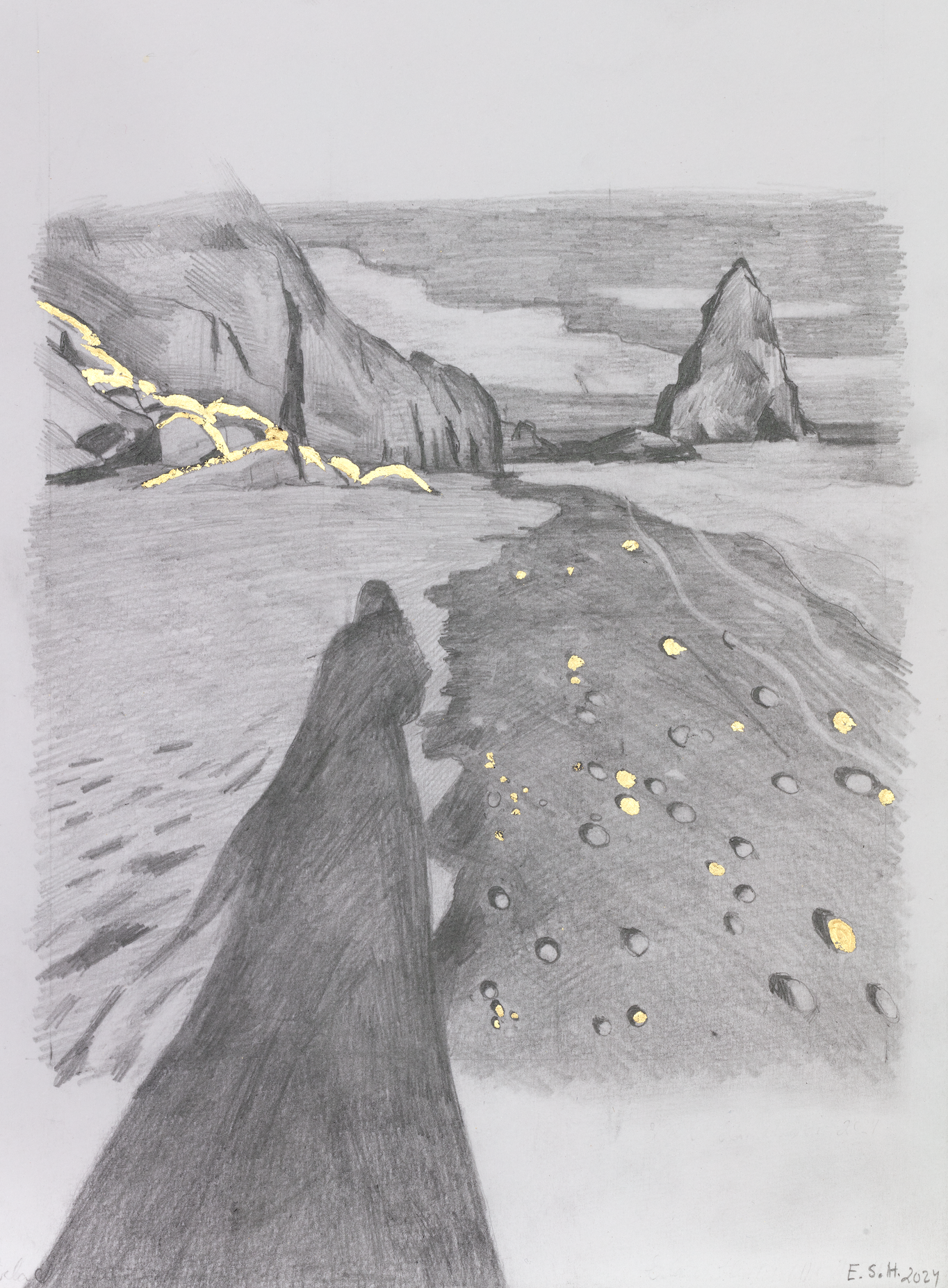

Erla Haraldsdóttir’s autobiographical and autoethnographic project My Mother’s Dream revolves around a dream that her great-great grandmother had when she was a teenager. It consists of a book with the diary entry with which the artist’s greatgrandmother records her mother’s dream and of a series of large-format paintings and smaller sketches that illustrate sequences from a kinswoman’s dream from around the year 1858.

The dream unfolds as a series of encounters with “hidden people,” as elves or fairies are called in local Icelandic belief. The book contains a facsimile of the diary entries, a photograph of the artist’s great-great-grandmother and great-grandmother, and translations of the dream into a matrix of languages that Haraldsdóttir has encountered in her lived experience in recent years, namely, English, Swedish, Icelandic, German, and isiNdebele (a Bantu language of South Africa). Dominant and minoritarian languages form a basis for different readings and transcriptions—Derrida’s “originary prints”— and this text of the unconscious is likewise valorized by the artistic process of its translation into pigment on canvas, or paper, or wall. Text and textile merge as family matters, women’s work, and what C. G. Jung would call an archetypical dream that taps into the collective unconscious are coming into focus. The familial and private thus strives towards the collective public and symbolic. But it doesn’t end there, as My Mother’s Dream has a reverse side My Dream, consisting of blank pages that invite readers to record their own unconscious dreamscapes.

The dream deals with birthing: the husband of a “hidden woman”/fairy mother seeks the help of a young girl (the dreamer) for his wife who is going into a difficult labor. The girl agrees to assist and in return is promised the gift of an intricate Icelandic traditional folk costume. But the fairy mother provides an injunction: the girl must never speak of this sequence of events in waking life. Naive as she is, she fails to heed this advice and is visited again later by the furious fairy mother, who takes back the folk costume. This traumatizes the dreaming girl to such an extent that she refuses to undergo confirmation, an important rite of passage into adulthood for Icelandic teenagers. How does the dream end? Twofold: after reconciling with the dreamer, the “hidden woman” tells her a secret blessed word for times of trouble; on her deathbed, the dreamer recounts her dream to her daughter, she did not reveal the secret of the blessed word of the “hidden woman” while retelling the stories of her encounters with her.

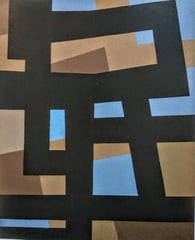

The distant, fairytale-like, unconscious material of these dreams is probed for the contents of this exhibition. It presents a new large-format painted diptych of the

“hidden woman”/fairy mother before and after the great-great-grandmother incurs her wrath. It also includes a mural that sits between the two parts of the painting. The English translation of My Mother’s Dream appears in a new series of works on paper that are illuminated manuscript pages in seven parts. A large-format painting, My Mother’s Dream, where the dream is recorded as a blown-up illuminated manuscript page, is presented for the second time after an exhibition at Nörrtalje Konsthall in 2021. Additionally, there are several inkjet prints of female reproductive organs merging with Icelandic folk costumes in a variety of colors. Last but not least, Haraldsdóttir is exhibiting for the first time a series of oil paintings of dream sequences and natural landscapes from Iceland in small square-format paintings.

Thus, the pure traces of an original unconscious writing take shape in a painting of the unconscious, an autoanthropology of the unconscious, and a questioning of the self, kinship, womanhood, and language.

Craniv Boyd